Native American Heritage, Today and Tomorrow

November is Native American Heritage Month, and it seems appropriate that this month’s election made history with Native American women elected to serve in Washington.

New Mexico’s Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo Tribe, won her House re-election bid. Yvette Herrell, a member of the Cherokee Nation, also won her seat representing New Mexico’s 2ndCongressional District. In 2018, Haaland, along with Kansas’ Sharice Davids, a member of the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) people, were the first two Native American women ever elected to Congress.

Congresswoman Deb Haaland

By U.S. House Office of Photography - [1], Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76965310

Congresswoman-Elect Yvette Herrell

By New Mexico House of Representatives -

https://www.nmlegis.gov/Members/Former_Legislator?SponCode=HHERY, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90968037

Congresswoman Sharice Davids

By Kristie Boyd; U.S. House Office of Photography -

davids.house.gov, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75879533

The fact that it took nearly 250 years for this to happen in the United States may not be surprising, as most are aware of at least some of the difficulties encountered over the years, the cultural bias endured, and obstacles overcome for Native Americans. What will likely be surprising, however, are the leadership roles- achieved through the force of will, great dedication and against fearsome hardships-- that female Native Americans have achieved in Native America society.

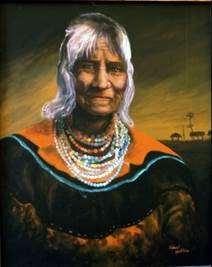

Betty Mae Jumper, First Female Chairperson of the Seminole Tribe of Florida

As we honor Native American Heritage Month, any list of Native American leadership, whether focusing on women or not, would include Betty Mae Jumper. Born in a Seminole Camp near Indiantown, Florida in 1923, Betty Mae was given her mother’s surname under the Seminole matrilineal kinship system. She spoke both traditional languages, Mikasuki and Creek, and grew up listening to older members of the tribe telling stories passed down from ancestors at nighttime. Jumper wanted to learn to read and write English, but in the segregated schools of Florida, neither the black nor the white schools would accept Seminole children. So, she enrolled in a federal Indian boarding school in North Carolina.

Betty Mae Jumper became the first Seminole to earn a high school diploma and was the first to graduate from nursing school, earning her degree in 1946. She brought modern medicine to her people, dedicating herself towards improving healthcare for Florida’s Seminoles and later being named the tribe’s first Health Department Director.

Jumper was part of the original Constitution Committee established to allow the tribe to forge a path towards self-reliance via their own governing system. She traveled to Washington, D.C.—even today tribal members remember her journey in a modest wooden-paneled station wagon-- in pursuit of 1957’s successful federal recognition of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

Under the new sovereign establishment, Jumper was the first female member of the Seminole Tribal Council, and in 1967 was elected as the first Chairwoman of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. She was appointed by then-President Nixon in 1970 to the National Congress on Indian Opportunity, and later became a founder of the powerful Native American lobbying coalition force of 26 federally recognized tribes called USET (United South and Eastern Tribes).

Jumper was active in business and culture as well, she founded and edited the Seminole Tribune, was the author of two books, and recorded those stories she heard as a young girl to preserve them for future generations. She was awarded an honorary doctorate degree by Florida State University in recognition of her continuing dedication towards improving the health, education, cultural and economic conditions of the Seminole people.

Portrait of Betty Mae Jumper, April 27, 1923-January 14, 2011,

first female chief of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

Photo credit: State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

http://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/4263

At her funeral service in 2011, son Moses Jumper said of his mother’s accomplishments, “… they told her she couldn’t do those things. It gave her more willpower and more energy.”

Today, her name lives on in tribal history—and in the hurricane-resistant, state-of-the-art 40,000 square foot Betty Mae Jumper Medical Center in Hollywood, which is a fitting tribute to a remarkably powerful female Native American leader.

Polly Parker: A Life Unconquered

Remarkable as well is the story of Polly Parker, one that is set against the backdrop of the Third Seminole War (1855-1858), the last in a series of conflicts that would become the longest and most expensive of the Indian Wars in United States History. Florida’s Seminole people continued to resist United States’ government efforts to surrender and submit to relocation, assimilation and cultural annihilation. No peace treaty was ever signed between the Seminoles and the United States government before, during, or after these Wars, a fact reflected even today in the tribe’s nickname, “The Unconquered.”

As the Seminole Wars progressed, the remaining Seminole men, women and children were forced to spend their lives hiding from the United States military forces ever deeper in the swamps and Everglades of Florida. The third Seminole War saw U.S. scouting parties directly encroaching on Seminole lands, destroying towns and cultivated fields to deplete the tribe’s food supply. Soldiers were ordered to forcibly relocate any tribal members who could be captured.

Polly Parker was taken to the prison at Egmont Key near Tampa. She, along with 163 other Seminoles, would be put aboard the Grey Cloud, a veteran steamship with more than two dozen relocation journeys. The Grey Cloud would head for New Orleans, with its hull filled with captured Seminoles. Then, the ship would steam upriver towards Arkansas. And finally, the journey transitioned to the long and often deadly walk remembered today as the “Trail of Tears.”

The Seminoles’ final destination was to be the Indian Territories of Oklahoma, land that was set aside by the U.S. Government specifically for the mandatory relocation of Native Americans. The law at the time required this, as it forbade any Native American to be anywhere east of the Mississippi River.

With Polly Parker on board, the Grey Cloud left Egmont Key, with a planned stop just south of Tallahassee at St. Marks for fuel and supplies. Along the way, Parker had successfully demonstrated her ability to use plants and herbs to treat some of the ailments of her captors.

At the St. Marks fueling stop, Parker asked to go in search of herbs to continue to practice her medicine. The fact that she had been successful in her efforts and not tried to escape may have caused those keeping her in custody to relax their guard. She was given permission to leave the ship, with only a single soldier accompanying her. Once she reached the woods, Parker was able to escape, successfully evading the efforts of dogs and a posse that chased after her for weeks.

Parker traveled at night, eating only what she could glean from the land. She ultimately traveled alone more than 300 miles, arriving back with her people in South Florida at Fish-eating Creek near Lake Okeechobee.

Polly Parker lived until 1921-- more than 100 years of age-- long enough to see Florida name a county after her people. Her descendants today number into the dozens—and include S.R. Tommie, Founder of Redline Media Group.

“Polly Parker was my great-grandmother,” said Tommie. “A true Seminole, and a true American as well. An amazing woman who single-handedly helped write—and indeed create-- the story of today’s Seminole Tribe of Florida. She refused anything less than a life of liberation, and I’m so very proud that her unconquered spirit lives on in me and in my Seminole brothers and sisters. I believe her story can serve as a beacon for those who face and overcome adversity—especially women. Polly Parker showed it is possible to achieve the impossible.”

Polly Parker (Emateloye)

Photo Credit Florida Department of

State